| The Ottendorfer Library |

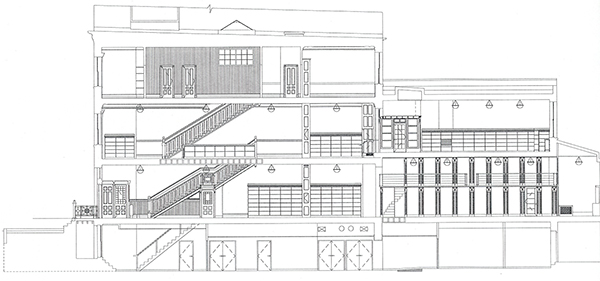

In 1883 the philanthropists Anna and Oswald Ottendorfer purchased a parcel of land at 2nd Avenue and 9th Street in what was then the heart of the German immigrant community in New York and engaged William Schickel as architect. The site was just a few blocks from the Astor Library at Lafayette Street, just north of 8th Street, New York's first public library. The site is twenty feet wide and 120 feet long, with the original building occupying eighty feet of the lot depth. While the building retains certain elements of the residential townhouse type, Schickel was clearly seeking ways to express the new public library type that was just then beginning to emerge.

The Queen Anne style staircase is located on the side and three arcuated Italianate windows facing the street on the upper floors articulate what would be, in a townhouse, the principal rooms of the residence. However, Schickel placed the main door in the center of the composition, emphasizing it with a large elliptical window above. This arrangement is fundamentally at variance with the residential type (except as found in very wide and deliberately grand structures) since in a residential building the door must be placed on the side, leading to the staircase, in order to allow maximum room for the living spaces.

Although the Ottendorfer was originally a closed stack institution, with books being brought by library staff to the borrower, the library was such a success that the radical step of converting it to an open stack operation was taken in 1885.

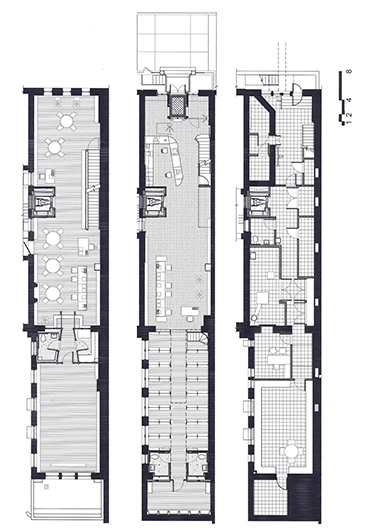

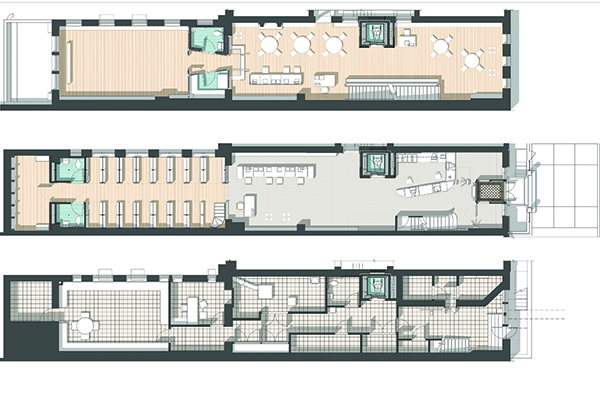

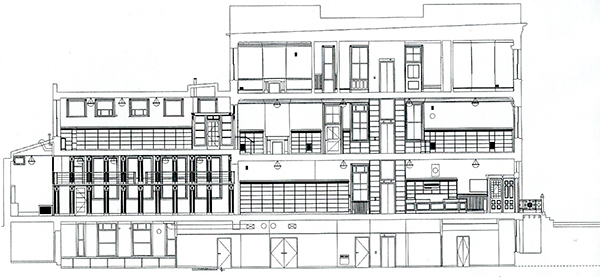

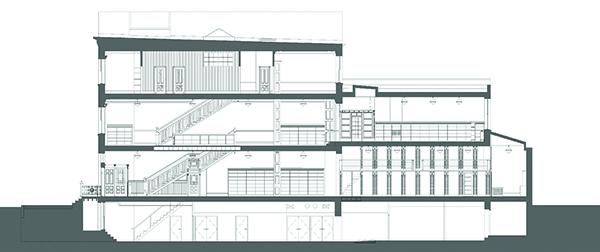

In 1899 the library was extended with a longer, two-level book stack, so that it now occupied the full 120 feet of the lot. The extended building represented a further evolution of its public nature, since in plan it would now be clearly unsuitable as a residence. Even more importantly, the separation of the reading areas from the book stacks, the separation, that is, of a space of edification from that of data storage, and the development of an architectural expression for each area, mark the library as fundamentally modern in organization.

The Ottendorfer did not conform to any contemporary library standards by 1998, when renovation of the landmark building was begun. In the modern New York library half the space, most typically on the second floor, is devoted to children's services. In addition, the local community is now multi-ethnic and requires books in dozens of languages rather than the original two northern European languages (English and German) of a century ago; an elevator is indispensable, for the management of the large number of books now circulated extensively between branch libraries, and because it is a legal requirement of the American's with Disabilities Law. Also, provision of computer access to information is now at least as important as information obtained through books themselves. In all these respects, as well as in others relating to administrative offices, bathrooms, light and mechanical systems, the library required extensive change.

The new front desk and elevator were located on the wall opposite the restored staircase, and one sees through these two opposing architectural set pieces into the main reading room with its new perimeter bookcases, lighting system and central reading and computer tables; beyond the reading room are book stacks with the new administrative quarters at the far end.

The book stacks that were added to the library at the turn of the century are of cast iron with plate glass floors. They introduce a language of early industrial modernism to the building and in their serial arrangement are symbolic of processes of repetitive fabrication, as opposed to the ultimately humanistic references of the earlier private Italianate library. One can see the origin of such an industrial vocabulary in the great magasin central, the book stack hall of the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris of Henri Labrouste completed from 1858 to 1868, which Schickel would certainly have known, having been trained in Germany in the 1850s. This late nineteenth century language of metal and glass was used as the starting point for the design of the new elevator enclosure, but updated to the present. It is clad in a grid of stainless steel and glass panels, whose proportions refer to those of typical bookcases. Rather than books, however, each panel within the grid holds the names of authors printed on rice paper laminated between glass sheets. The elevator enclosure forms a tower of knowledge rising through the building, and identifies 365 of the world's greatest writers from all geographical locations and times.

The elevator rises through the full height of the library from the new basement administrative areas to the staff lounge on the third floor. The elevator was placed on the north side of the building, and creates on each of the main floors a front and back area. On the ground floor the distinction is between the area of arrival, checkout, security and circulation and the reading room. On the second floor, it separates the young children at the front from older children and computer stations at the rear. Beyond this area is the new "story hour" room for programs designed for children of all ages. Separating this room from the children's reading room are the children's librarian's office and the children's bathroom.

The Ottendorfer Library shows how the original transformation of a residential type into an institutional one can be adapted through time once a new typology has been clearly established. In this case, the new type was established by 1900. Within this type, the renovation design has been able to absorb such changes as the need for children's programs due to changing social patterns among parents, the accommodation of the electronic information age and the modern pluralism of ethnicity. These changes have enabled the Ottendorfer Library to remain New York's oldest continuously operating public lending library.